(Where Dense Search Becomes a Distributed Systems Problem)

Most content about vector databases focuses on the glamorous part: fast queries, clever indexing, tight cosine similarity loops.

But if you operate these systems in production, you learn something uncomfortable:

Your system’s correctness, performance, and scalability are defined far more by the write path than by the read path. Dense vector search looks like a retrieval problem. In reality, it’s a distributed systems problem wearing an information-retrieval disguise. This post breaks down how different indexes actually handle writes, why reindexing is so expensive, and what architects must plan for long before deploying a vector DB into RAG, agent workflows, or search systems.

1. Why the Write Path Is the Real System Bottleneck

Every time you insert a new vector, three things must happen:

- The index must place it correctly in the ANN structure.

- The system must update search metadata so routing and lookups remain correct.

- The system must preserve recall guarantees despite the new insertion.

These sound simple. They aren’t.

Different ANN structures handle writes in completely different ways — and their behavior under load defines the architecture around them.

Let’s walk through what actually happens under the hood.

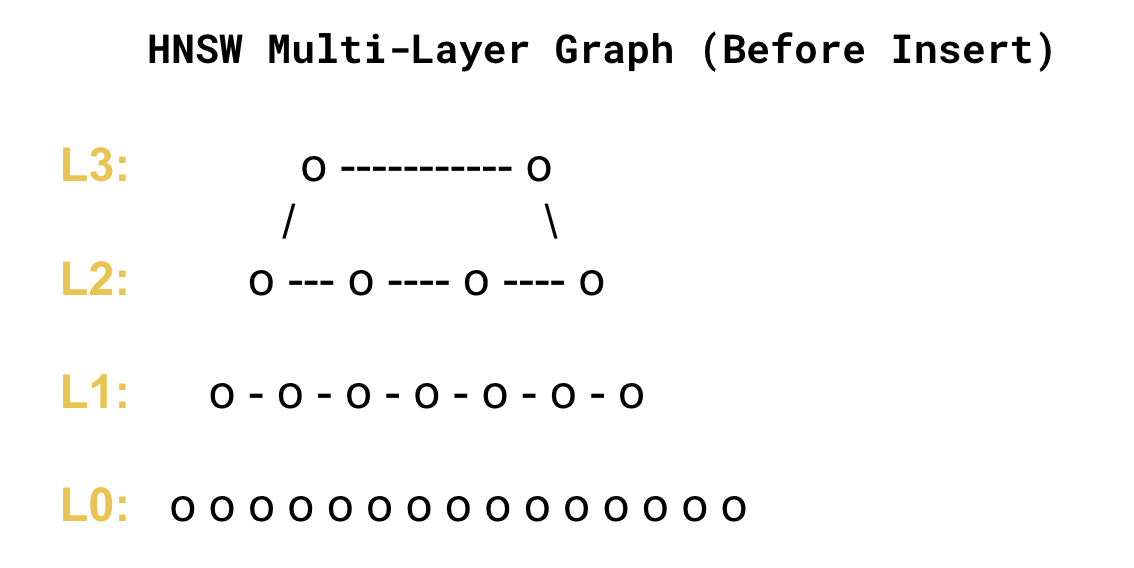

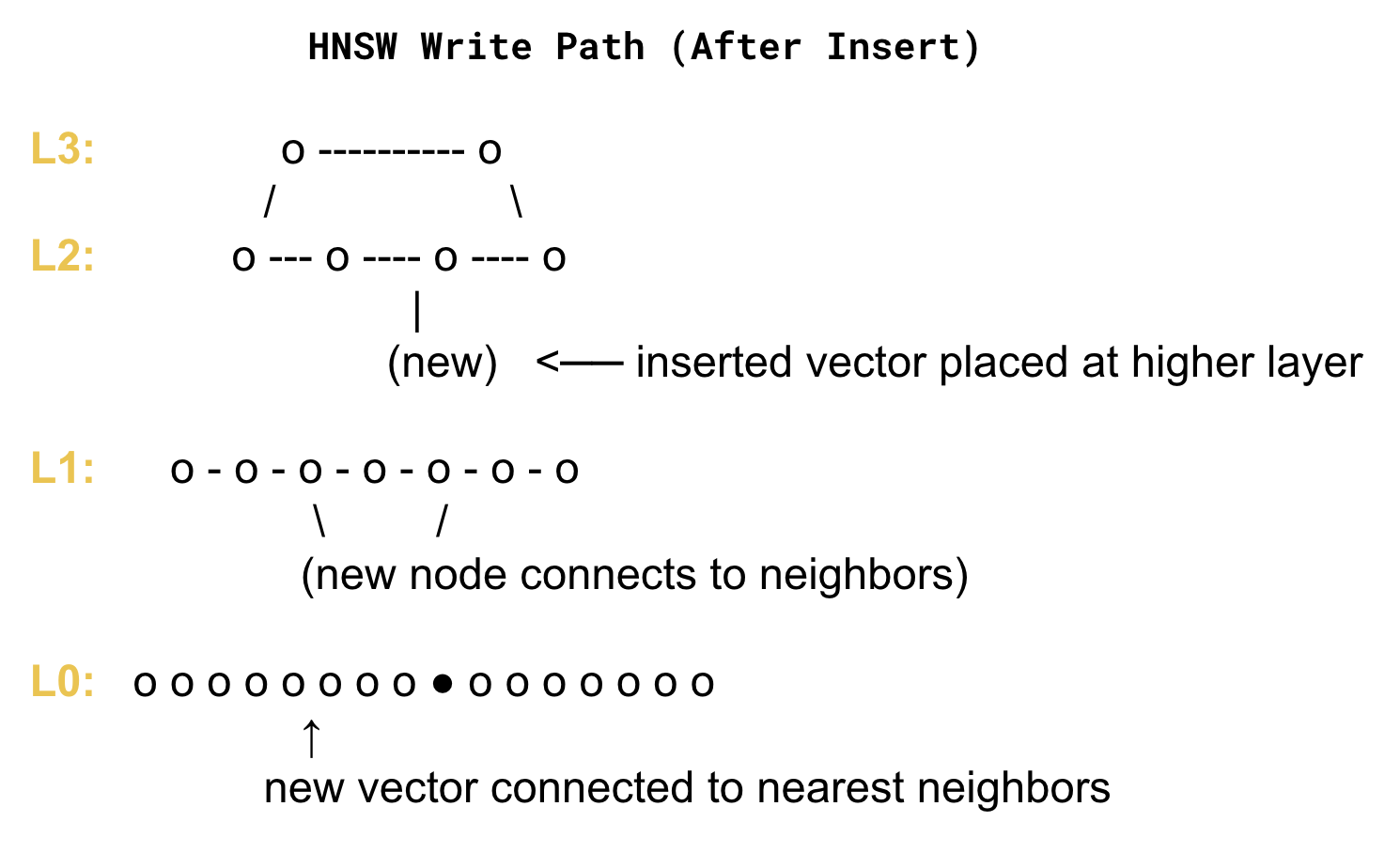

2. HNSW Writes: Modifying a Live Graph

HNSW isn’t a tree, or a cluster, or a table. It’s a multi-layer graph with strict structural invariants. When you insert a single vector, HNSW must:

- connect it to its nearest neighbors

- place it in a hierarchy where upper layers are sparse and lower layers dense

- ensure no layer becomes disconnected

- update multiple candidate lists along the path

This is not a constant-time operation. It’s not even predictable.

Why HNSW Writes Are Slow

Because the graph must maintain high recall, every write involves:

- repeated distance computations

- adjusting edges

- preserving graph navigability

- ensuring top-level shortcuts remain meaningful

If you insert too quickly, the graph “churns” — quality drops, recall drops, and the system starts reorganizing itself behind the scenes.

This is why real-world HNSW deployments almost always adopt the same pattern:

HNSW is best served as a mostly-static graph, requiring separate ingestion lanes and periodic full merges to manage churn. It’s the only way to avoid corrupting recall under sustained write pressure.

3. IVF Writes: Where Predictability Comes From

IVF takes the opposite approach. Instead of maintaining a global structure, IVF says:

“We’re going to cluster the vector space once…”

“…and every new vector goes to the nearest centroid.”

So a write is:

- Embed vector

- Find nearest centroid (K comparisons)

- Append to that cluster

- Update local metadata

That’s it. No global edges, no multi-level rebalancing, no graph mutation.

Why IVF Writes Are Fast

Appending to a cluster is structurally simple. This makes IVF the backbone of distributed vector databases like Pinecone and Weaviate. Writes scale horizontally, shards map directly to clusters, and routing stays predictable.

The tradeoff is cluster drift — if your embedding distribution changes enough, vectors that used to belong together don't anymore. Think of it like sorting emails into folders based on keywords ten years ago. If the underlying vocabulary or product line has fundamentally shifted, the old folders are now a poor map of the new incoming vectors.

And when that happens, recall quietly drops… until you re-cluster.

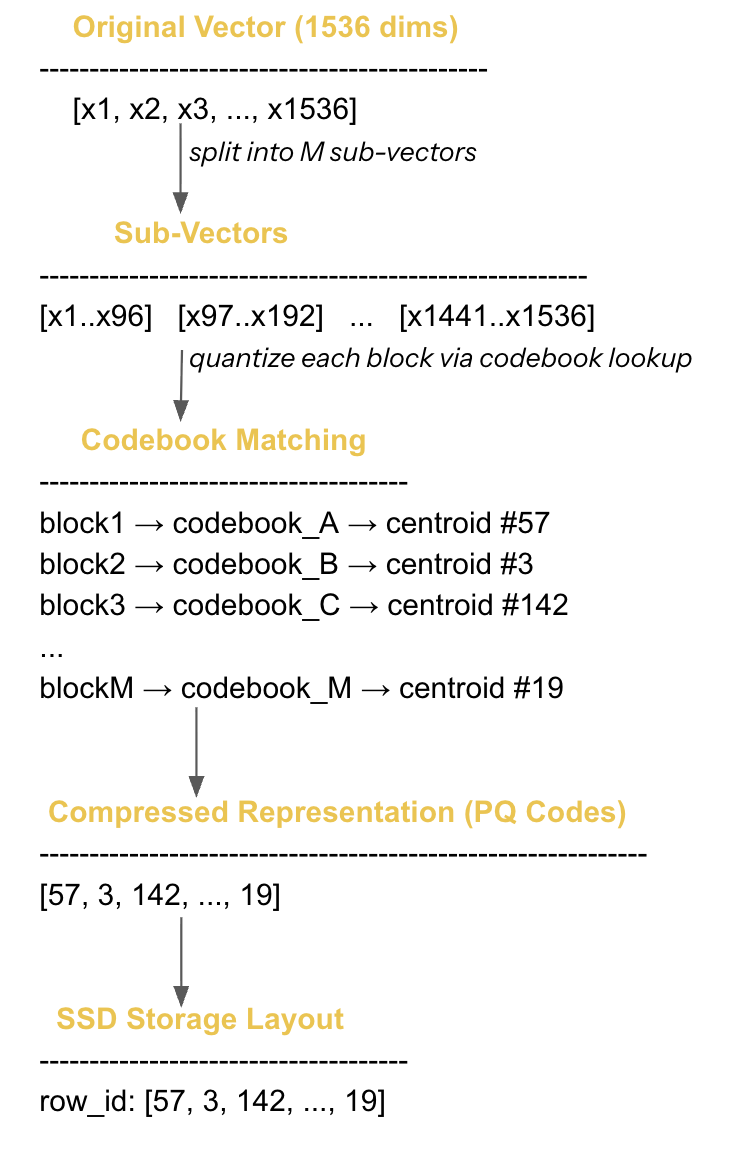

4. PQ/OPQ Writes: The Most Expensive Pipeline in Vector Search

If HNSW is slow because it maintains a graph, PQ is heavy because it maintains a compression model.

A PQ write looks like:

- Embed vector

- Split into sub-vectors

- For each sub-vector, find the nearest “prototype” in its codebook

- Convert that into an integer code

- Store those codes on SSD in a compressed layout

- Update metadata for decompression, re-ranking, and refinement

If you’re using OPQ, there’s an extra step:

- rotate the vector using a learned transformation matrix before quantizing

This single matrix multiply adds substantial cost per write.

Why PQ Writes Hurt

- Codebook lookup = expensive

- Quantization = lossy

- Storage layout = SSD-sensitive

- Updating codebooks = expensive

- Maintaining recall = tricky

Which is why PQ is rarely used for ❌ real-time ingestion ❌ high-write systems ❌ rapidly evolving datasets.

But it is perfect for: ✔ billion-scale catalogs ✔ archive systems ✔ low-write, high-read workloads where memory footprint is the primary constraint.

PQ is a power tool — but not a general-purpose ingestion engine.

5. Why Reindexing Is a Cluster-Wide Event (Not Maintenance)

Reindexing sounds simple:

“Let’s rebuild the index with the new embeddings.”

In a dense vector system, this is the equivalent of saying:

“Let’s rebuild the entire distributed search engine, all routing metadata, all clusters, all centroids, and all replicas.”

Furthermore, the index build itself is a massive, resource-intensive compute job that can saturate CPU and memory across an entire cluster.

Reindexing happens when:

- You change the embedding model

New model = new geometry.

All distances change.

Cluster boundaries change.

Graph edges become invalid.

Codebooks stop matching.

Everything breaks, so everything must be rebuilt. - You change dimensionality

Moving from 768 → 1536 dims means:- different memory profile

- different distance distribution

- different quantization shape

Again: rebuild.

- Your domain changes (vector drift)

Embeddings drift naturally as:- product lines change

- vocabulary shifts

- user-generated content evolves

This breaks clusters and codebooks over time.

- You need better recall or lower latency

Sometimes you must:- increase K (cluster count)

- adjust HNSW link factor (M)

- recompute codebooks

Every one of these implies a rebuild.

6. Why You Cannot Reindex In Place

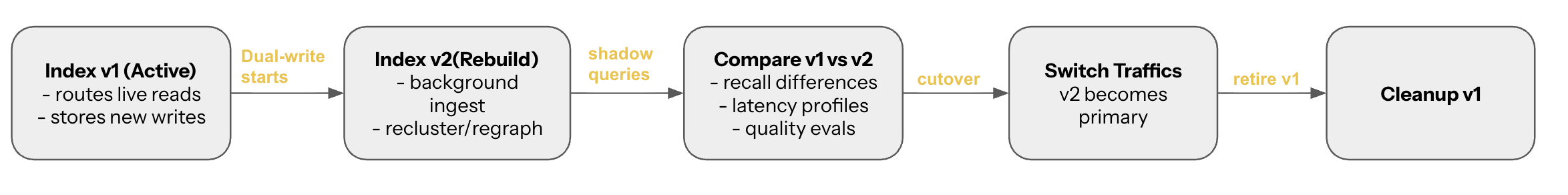

A production vector DB must behave like a distributed search engine: You need:

- Versioned indexes (v1, v2, v3…)

- Dual-write (ingest into both indexes)

- Dual-read (compare quality, run shadow queries)

- Background rebuilds (no downtime)

- Cutovers (switch traffic atomically)

- Rollback paths (if v2 performs worse)

This is almost identical to:

- Lucene reindexing

- search cluster migrations

- schema-level DB migrations

Except vector DBs have:

- heavier compute

- more sensitive distribution

- larger data volumes

- more complex routing metadata

Reindexing is not an ML operation. It is a full distributed systems migration.

7. The Long-Tail Problem: Where Quality Quietly Degrades

Even when your writes “work,” the system accumulates small structural imperfections from inserts, updates, and deletes:

- HNSW edges degrade

- IVF clusters drift

- PQ codebooks become stale

- Routing becomes less accurate

- Shards grow unevenly

- Replicas diverge

Updates and deletes rarely happen in-place; they often require expensive marker flags, increasing read latency, and necessitating periodic compaction or full index rebuilds. This degradation is slow, quiet, and dangerous.

A healthy vector system must run:

- background refinement jobs

- centroid realignment

- codebook drift correction

- shard rebalancing

- compaction tasks

- ingestion burst smoothing

These tasks keep search quality predictable.

Final Takeaway

Search is easy. Writing is hard. If you ignore write-path design, you don’t have a vector architecture — you have a vector demo. A production vector database must treat the write path as a first-class architectural layer, because:

- graphs mutate unpredictably (HNSW)

- clusters drift (IVF)

- codebooks decay (PQ/OPQ)

- embeddings shift (drift + new models)

- routing depends on metadata that must stay consistent

Dense vector search begins with embeddings… but it succeeds or fails on the write path.