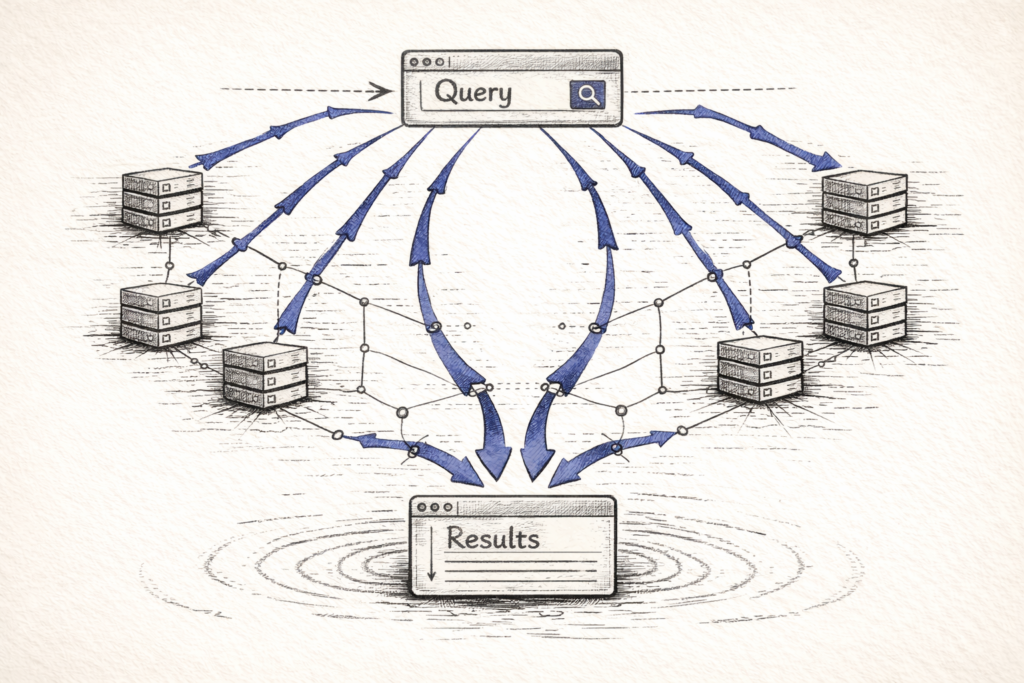

Why dense search becomes a routing, sharding, and distributed-systems problem

Vector search looks simple when everything fits on one machine.

It becomes a different discipline entirely when you need to serve:

- millions to billions of vectors,

- across multiple nodes,

- with predictable latency,

- and high recall,

- while RAG or agent pipelines depend on you staying under 100ms end-to-end.

Unlike relational data, vectors can’t be sharded by key.

Unlike document search, they don’t map cleanly to inverted indexes.

And unlike hash tables, you can’t just spread them uniformly and hope locality survives.

Nearest neighbors live in geometry, not in keys — and geometry doesn’t respect your shard boundaries.

This post explains how distributed vector systems actually scale.

Once you understand this, you understand the architecture behind Pinecone, Weaviate, Milvus, Qdrant, Vespa, pgvector clusters — and every serious internal enterprise vector engine.

1. Why Distributed Vector Search Is Harder Than It Looks

Every distributed vector database must answer three questions:

1. How do we split vectors across machines? (Sharding)

2. How do we send each query to the right machines? (Routing)

3. How do we merge partial results correctly? (Aggregation)

The Annoying Trade-Off: Achieving the highest Recall usually requires a wider search (more shards/nodes), which directly conflicts with the need for low Latency and low Cost (less fan-out). Distributed vector search is primarily an optimization problem trying to balance this triangle.

If any part breaks:

- recall silently drops,

- latency becomes unpredictable,

- RAG pipelines hallucinate,

- agent behavior drifts,

- and costs explode.

Everything starts with sharding.

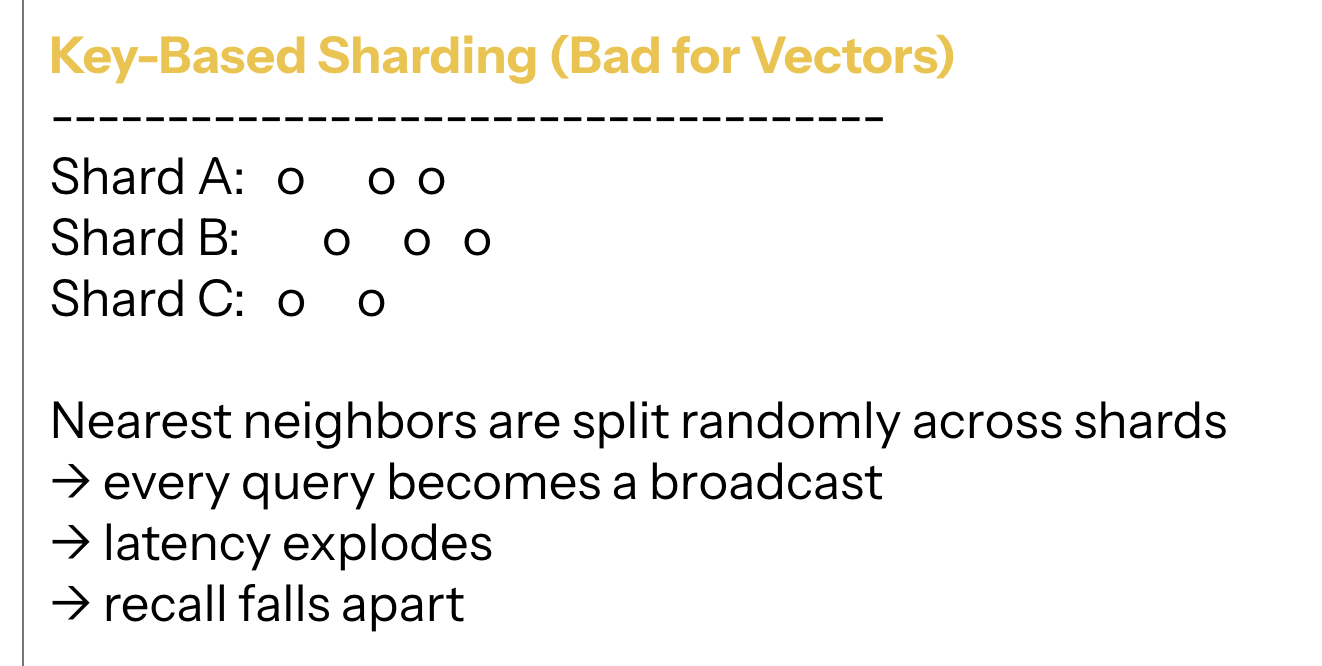

2. Sharding: How to Divide Vectors Without Destroying Locality

In distributed systems you normally choose a key, hash it, and assign it to a shard.

Vector search makes that impossible.

Why?

Because neighbors aren’t defined by a key — they’re defined by position in high-dimensional space.

Random hashing destroys that.

So modern vector DBs rely on three sharding strategies.

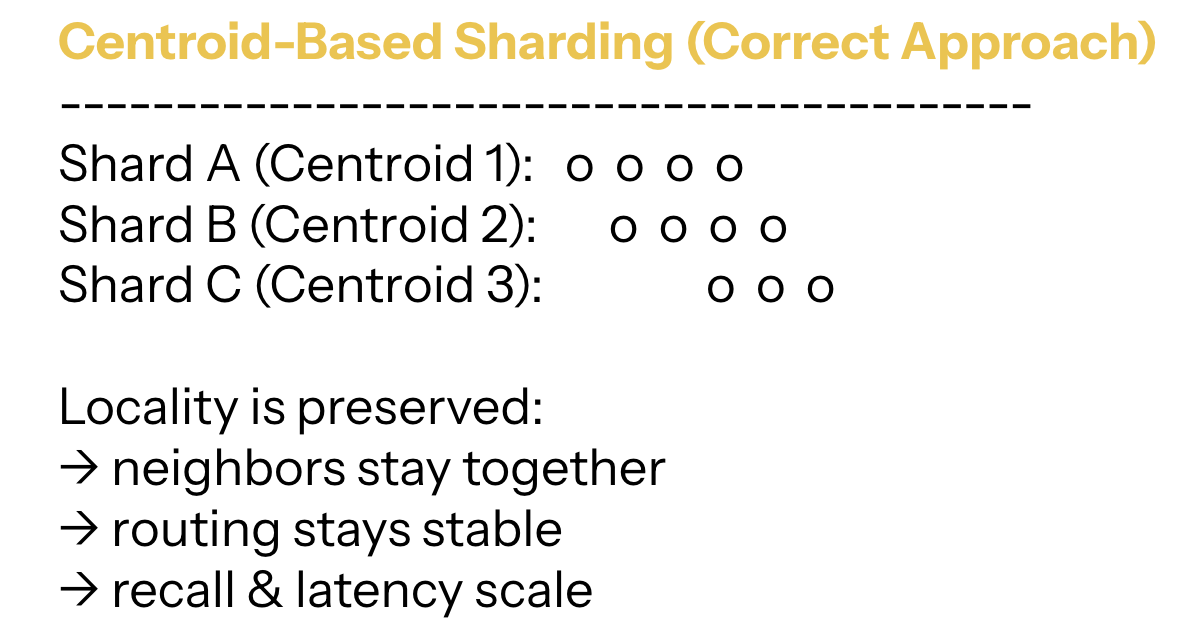

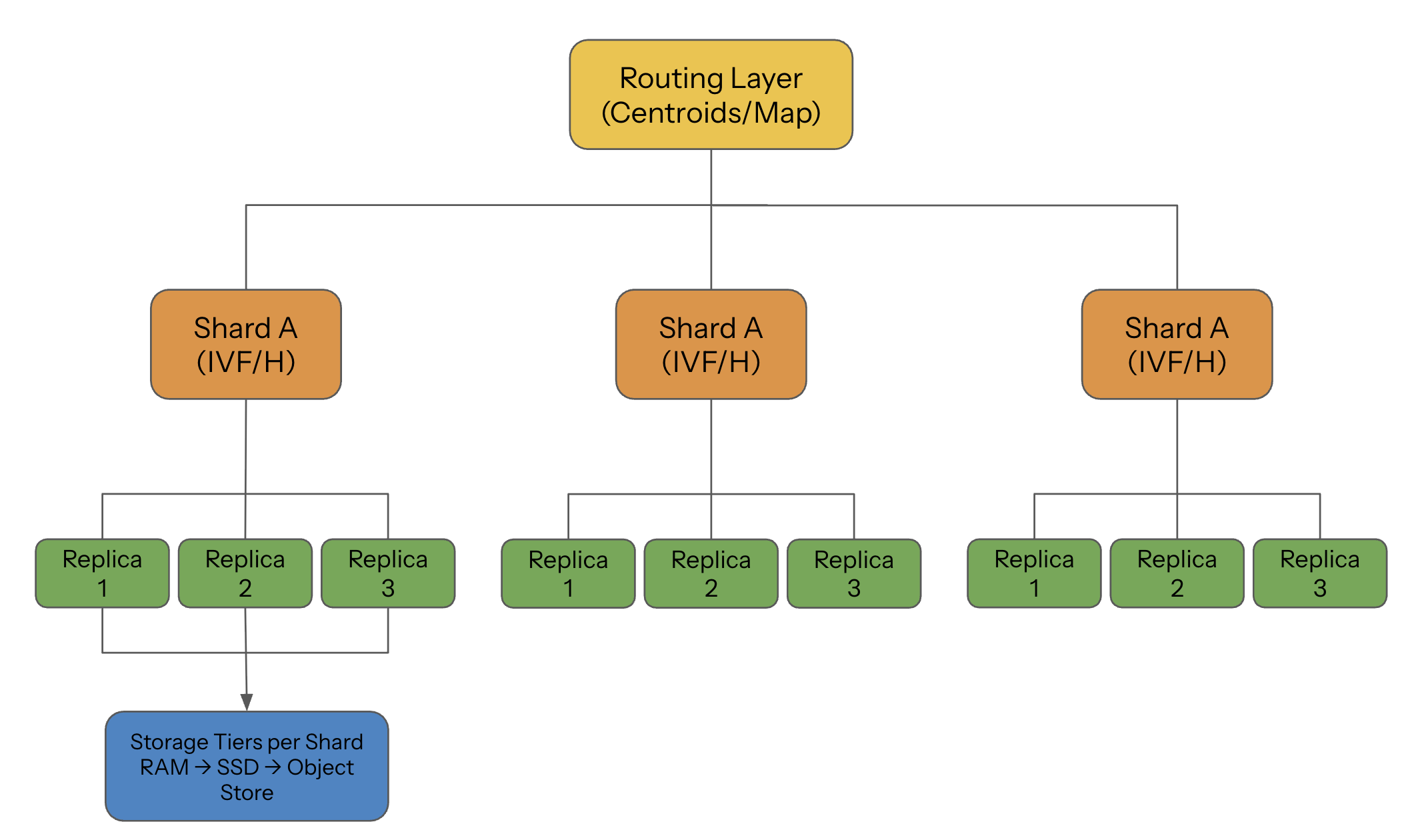

2.1 Centroid-Based Sharding (IVF): The Scalable Default

This is the dominant approach in the industry.

The idea:

- Cluster the entire dataset into K coarse clusters.

- Assign each cluster to a node or shard.

- Put each vector in the shard corresponding to its nearest centroid.

This preserves locality almost perfectly:

vectors that live near each other in space end up on the same node.

Why it works so well:

- Locality is preserved → fewer shards per query.

- Routing is simple → “send the query to the clusters closest to the query centroid.”

- Scaling is linear → want more throughput? increase the number of clusters.

This is why IVF underpins Pinecone pods, Milvus distributed mode, Weaviate’s sharding, and several proprietary internal search engines.

It’s simple, elegant, and incredibly effective.

2.2 Graph-Aware Sharding (HNSW): The Hard Path

HNSW is a global graph — a network of vectors connected by distance-based edges.

Graphs don’t shard cleanly.

If you cut the graph across machines:

- long-range links break

- neighbor connectivity weakens

- navigation steps increase

- recall collapses

To avoid that, HNSW systems typically:

- use fewer but larger machines,

- rely heavily on replication rather than partitioning,

- reindex periodically in large batches,

- avoid high-rate streaming writes.

That’s the tradeoff: you get microsecond-level search but pay for it in distribution complexity.

Emerging Approaches: Some advanced systems use Hierarchical Sharding, employing IVF for the coarse, top-level routing, and then running HNSW within each resulting shard. This combines the sharding efficiency of IVF with the high-speed local search of HNSW.

2.3 Hybrid Sharding (Metadata + Geometry)

Real products have constraints that pure geometry can’t solve:

- tenant separation

- compliance + PII boundaries

- billing isolation

- organizational ownership

- domain-based access controls

So enterprises combine keys:

- (cluster_id, tenant_id)

- (centroid_id, time_bucket)

- (domain, cluster_range)

This balances locality and organizational constraints.

Sharding is no longer an IR decision.

It becomes a business + cost + compliance architecture decision.

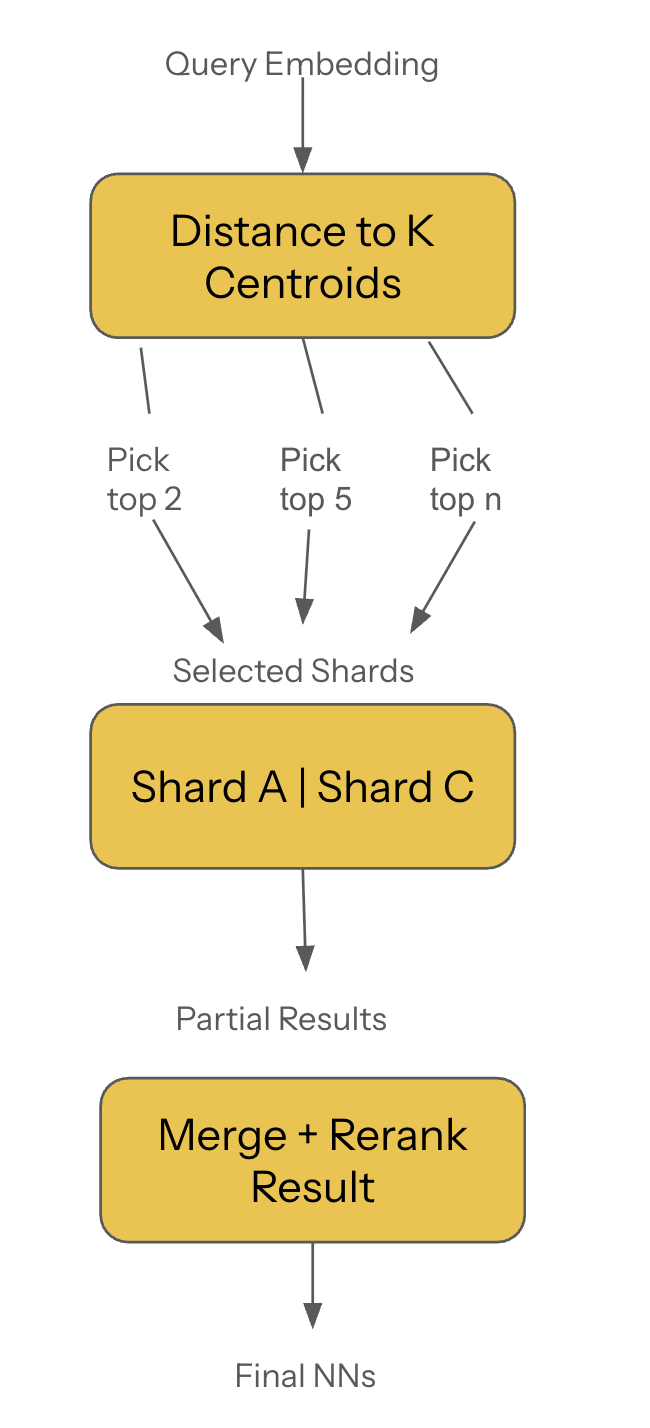

3. Routing: How Queries Find the Right Machines

Once the data is split, the next problem appears:

Given a query embedding, which shards are worth searching?

You cannot search all shards.

Broadcasting destroys latency and cost.

Three routing strategies dominate.

3.1 Centroid-Based Routing (Most Common and Most Efficient)

The workflow:

- Embed the query.

- Compare it to the centroid set.

- Pick the closest clusters (nprobe).

- Route to only those shards.

Benefits:

- tiny and predictable fan-out

- stable latency

- near-linear scalability

- excellent recall when tuned correctly

The tunable nprobe value is the primary control knob for balancing latency and recall in IVF-based systems.

3.2 Full Broadcast (The Anti-Pattern)

When systems lack routing metadata — or when developers don’t know any better — they do:

send query → hit all shards → merge everything

This is only tolerable for:

- tiny datasets

- hobby work

- toy deployments

For real workloads, broadcast guarantees:

- inflated CPU usage

- runaway latency

- unpredictable tail behavior

Avoid unless you enjoy on-call rotations.

3.3 Learned Routing (Emerging Trend)

This is the frontier:

- ML models that predict the best shard

- neural networks that learn routing boundaries

- secondary vector indexes over centroids

- adaptive fan-out controllers

Early research shows:

- lower fan-out

- more stable latency

- better load distribution

Expect this to reach production over the next 1–2 years, especially in multi-tenant workloads.

4. Replication: Keeping the Cluster Alive Under Failure

Vector databases replicate for:

- high availability

- fault tolerance

- higher read throughput

- isolation between workloads

But the replication cost is very different depending on the index.

4.1 HNSW Replication: Heavy and RAM-Hungry

Replicating a graph means copying:

- vectors

- edges

- multi-layer structures

Snapshotting and restoring HNSW can be slow.

Keeping replicas consistent under writes is harder.

Most systems compromise:

- active–passive pairs, or

- active–active with diluted consistency.

4.2 IVF Replication: Smooth and Cheap

IVF shards are just lists of cluster partitions.

Replication is simply:

- copy partition → refresh metadata → done.

Fast and reliable.

This is why IVF is a favorite for distributed, HA deployments.

4.3 PQ Replication: Storage-Heavy, IO-Sensitive

PQ compresses vectors into blocks stored on SSD.

Replication requires copying:

- compressed codes

- codebooks

- SSD block layouts

Less RAM cost, more IO burden.

PQ is not a graph challenge; it’s a storage + wear-leveling challenge.

5. The Write Path: Sharding Vectors as They Arrive

The challenge of distributed search isn't just serving queries; it's efficiently inserting new data. The write path introduces a critical bottleneck:

- Global Lookup Requirement: For Centroid-Based (IVF) systems, a newly ingested vector must first be compared against the global centroid index (the small, centralized structure) to determine its correct shard. This global lookup structure must be extremely fast, highly available, and consistent, as it acts as the central routing layer for all incoming writes.

- Consistency and Latency: Once the shard is identified, the write must be propagated to all its replicas. For graph-based indices like HNSW, maintaining read/write consistency across replicas during high-volume streaming writes is a significant source of operational complexity and write-side latency.

6. Multi-Tier Storage: RAM → SSD → Object Store

Scaling vector DBs requires understanding that not all vectors need to live in RAM.

Modern systems use tiered storage:

RAM (hot path)

- centroids

- routing tables

- top-level HNSW layers

- PQ codebooks

- hot vectors

SSD (warm path)

- IVF partitions

- compressed PQ blocks

- overflow segments

Object Storage (cold path)

- historical embeddings

- archive partitions

- old index versions

- rebuild artifacts

The key idea:

RAM is for navigation. SSD is for capacity. Object storage is for history.

7. Latency Budgets: The 100ms Constraint

In RAG and agent pipelines, vector search is just one stage.

The entire system must fit inside a 100–150ms window.

Typical budget:

- embedding model → 10–50ms

- vector search → 5–30ms

- reranking → 5–15ms

- LLM → 30–80ms

If vector search burns 40ms, the pipeline breaks.

This is why distributed search must:

- keep fan-out tiny

- minimize inter-node chatter

- ensure shard latency consistency

- avoid broadcast

- use caching and prefetch for PQ

Latency is not an optimization problem — it’s a survival constraint.

Final Takeaway

Distributed vector search is not “just ANN at scale.”

It is:

- geometry

- sharding strategy

- routing correctness

- replication mechanics

- tiered storage

- workload isolation

- latency budgeting

- operational discipline

The deeper truth: Dense search is a distributed systems problem disguised as a retrieval problem. And ultimately, sharding and routing are your primary defense against spiraling infrastructure costs.

Once you internalize that, index tuning stops being the bottleneck — and architecture takes center stage.