Most people think dense vector search works like this:

- embed your documents

- store the vectors

- run cosine similarity

Done.

This is the biggest misunderstanding in modern AI systems.

Dense vector search looks simple, but in real deployments it becomes one of the hardest layers to scale—and often the true bottleneck behind:

- slow RAG pipelines

- inconsistent retrieval

- unpredictable agent latency

LLMs aren’t slow. Dense search often is.

ANN structures like HNSW, IVF, PQ, and OPQ fundamentally reshape how vector databases behave. Hybrid retrieval improves relevance, but dense search determines the baseline latency, memory footprint, and write cost—it determines whether your system can scale at all.

1. Dense Vector Search Looks Simple — But Isn’t

Embeddings convert text into high-dimensional vectors:

- OpenAI

text-embedding-3-large→ 1536 dims - Cohere → 1024 dims

- BERT family → 768 dims

- USE → 512 dims

So it’s natural to assume:

“They’re just arrays of floats — how hard can searching them be?”

The illusion of simplicity

A vector is just a list of numbers:

[0.12, -0.56, 1.44, ...] # 1536 dimensionsCosine similarity is a one-liner in NumPy:

scores = np.dot(query_vector, all_vectors.T)But this intuitive mental model collapses instantly when you scale.

Why the simplicity breaks

Dense vector search becomes difficult because:

1.1 High-dimensional geometry behaves badly

In 1536 dimensions:

- distances converge

- all points are “equally far”

- neighborhoods become unstable

This is the curse of dimensionality, and it destroys the intuition that makes “just run cosine similarity” seem reasonable.

1.2. Brute force is computationally impossible

For 10M vectors:

10M × 1536 dims × ~2 FLOPs per dim ≈ 30B operations/queryNo real RAG or agent system can afford that at interactive latency.

1.3. Memory becomes the real constraint

1 vector ≈ 6 KB ; 10M vectors ≈ 60 GB raw; Indexes → 100 GB+

Dense search is not compute-bound — it is memory-bound and topology-bound.

1.4. ANN indexing is mandatory — and index choice becomes architecture

You must use an ANN index:

- HNSW → fast lookups, heavy RAM, complex writes

- IVF → predictable shards and routing

- PQ/OPQ → billion-scale compression

- Flat → only for demos

The index you choose dictates:

- latency

- recall

- write-path cost

- replication model

- shard shape

- routing strategy

- reindexing cost

This is where vector databases diverge from simple “cosine search engines.”

1.5. Scaling beyond one machine turns dense search into a distributed systems problem

Once your data doesn’t fit on a single node, you now need:

- geometry-aware sharding

- centroid- or hierarchy-based routing

- replica consistency for ANN structures

- background rebuilds and compaction

- RAM/SSD tiering

- index versioning and cutovers

This is exactly where most RAG and agentic systems slow down or start failing.

Takeaway

Dense vector search is not:

- “Just store embeddings in a DB.”

- “Just use Pinecone.”

- “Just call cosine similarity on a GPU.”

It is search + memory + distributed systems engineering, tightly fused into a single layer.

2. Embeddings: Meaning as High-Dimensional Geometry

Dense vector search doesn’t start with indexes. It starts with embeddings — the geometric representation of meaning that everything else is built on.

To understand why dense search is hard, you need a clear mental model of what embeddings really are.

2.1 What Embeddings Actually Represent

An embedding is a numeric fingerprint of meaning.

When you embed text, you’re asking the model:

“Place this piece of text somewhere in a huge geometric space so similar meanings end up close together.”

So phrases like:

- “504 gateway timeout”

- “API timing out”

- “service latency escalation”

→ land near each other.

Low-dimensional (3D): High-dimensional (1536D):

Clusters form naturally. Clusters become thin and fragile.

● ● ● ● ● ● ●

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

● ● ● ● ● ● ●3D clusters look intuitive. In 1536D, geometry behaves very differently — we’ll get into that in Section 3.

2.2 Why Embeddings Have 512–3072 Dimensions

People often ask: Why 768? Why 1024? Why 1536?

It’s not arbitrary. The embedding dimension is the hidden size of the model.

Whatever the model’s final internal representation is → that becomes its vector.

Examples:

BERT-base: 768 dims

BERT-large: 1024 dims

Cohere: ~1024 dims

OpenAI 3-large: ~1536 dims

USE: ~512 dimsTakeaway

Higher dimensions usually give:

- better meaning separation

- smoother recall

- better clustering

But also:

- more memory

- more compute

- more curse-of-dimensionality behavior

Better embeddings → heavier infrastructure. There is no free lunch.

2.3 Memory Footprint — Where the Pain Starts

Each embedding is a list of floats. float32 = 4 bytes. So for 1536 dimensions:

1536 × 4 bytes = 6144 bytes ≈ 6 KB per vectorRaw memory requirements

| Vectors | Raw Size | With Index Overhead |

|---|---|---|

| 1M | ~6 GB | 8–12 GB |

| 10M | ~60 GB | 80–120 GB |

| 100M | ~600 GB | 800 GB–1.2 TB |

This is before:

- replication

- routing metadata

- index versioning

- write buffers

- caches

Vector databases are RAM-heavy by design because embeddings are. This unavoidable memory footprint is the first reason brute-force search collapses. The second is the fundamental failure of geometry.

2.4 Embedding Drift & Versioning (Real Production Concern)

Embedding models evolve:

- newer versions (OpenAI 3 → 3-large)

- dimensionality changes

- better chunking

- domain-specific finetunes

This causes embedding drift — the geometry of your vector space changes.

Why drift breaks search

Vectors from model “v1” can’t meaningfully be compared to vectors from “v2” because:

- distances shift

- neighborhoods change

- clusters move

- ANN recall silently collapses

What architectures must support

┌───────────────────┐

│ index_v1 (old) │

└───────┬───────────┘

│ dual-write

┌───────▼───────────┐

│ index_v2 (new) │

└───────────────────┘You now need:

- Versioned indexes

- Dual-write during transition

- Background re-embedding jobs

- Shadow / dual-read testing

- Rolling cutover + rollback path

This is not an “ML model update.” It’s a distributed system migration, with the retrieval layer as the blast radius.

2.5 Takeaway

Embedding dimensionality and drift create non-negotiable infrastructure constraints:

- Memory scales linearly with vector size

- ANN index choice depends on dimensionality

- Reindexing becomes a platform-level migration

- Distributed sharding and routing depend on embedding geometry

- Better embeddings → heavier system design

This section lays the foundation for why brute-force search collapses and why ANN indexes exist at all.

3. Why Brute-Force Dense Search Collapses

Dense vector search doesn’t break because embeddings are bad or because hardware is slow.

It breaks because high-dimensional geometry behaves nothing like human intuition, and brute-force similarity search collapses the moment your dataset grows beyond a few million vectors.

Let’s walk through this properly.

3.1 The Real Cost of Brute-Force Search

Naively, dense search is:

Compare the query vector against every stored vector.

Similarity (dot product / cosine similarity) requires:

score = Σ (query[i] * doc[i])Each dimension = 1 multiply and 1 add → 2 FLOPs

Concrete numbers

1536-dimensional vectors; 10M stored vectors

10,000,000 × 1536 × 2 = 30,720,000,000 operations/query ≈ 30.7 billion FLOPsEven with:

- a fast GPU

- optimized BLAS kernels

- contiguous memory

30 billion FLOPs per query is not survivable for:

- RAG calls

- multi-step agent loops

- chatbots

- semantic search

- enterprise dashboards

One agent loop might perform 5–10 retrieval steps → you’re now pushing 150–300 billion FLOPs for a single user action. This is the end of brute-force.

3.2 FLOPS Are Not the Real Bottleneck

People often say:

“GPUs can do tens of trillions of FLOPS — what’s the problem?”

Dense search is not compute-bound. It is memory-bound.

Why brute-force hits a wall:

- random memory access

- poor cache locality

- non-contiguous vector layouts

- oversized datasets (don’t fit in GPU RAM)

- PCIe bottlenecks

- NUMA crossing

- memory bandwidth saturation

The hardware can multiply quickly — it just can’t deliver the data fast enough. Even large GPUs spend more time fetching vectors than computing over them.

3.3 The Curse of Dimensionality

This is the geometry failure hidden inside dense search. Intuition:

In low dimensions (like 2D / 3D)

- clusters are obvious

- neighbors are meaningfully “close”

- distance metrics behave predictably

2D intuition:

● ●

● ●

● ●In high dimensions (768–1536)

Distances converge. Everything is almost equally far from everything else.

1536D intuition:

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

(nearly uniform distances)Consequences:

- neighborhoods evaporate

- the “nearest” and “farthest” points differ by tiny margins

- recall becomes unstable

- radius-based search becomes useless

- exact search becomes meaningless

High-dimensional geometry is fundamentally unintuitive. Formally, this is called distance concentration, where the ratio of maximum to minimum distance approaches 1. This instability means the true nearest neighbor is often separated from a non-relevant vector by a tiny, noise-dominated margin.

3.4 Why Exact Search Stops Making Sense

In high dimensions:

- distances collapse

- clusters smear out

- noise dominates

- everything lives near the surface of a hypersphere

- brute-force returns unstable nearest neighbors

This leads to the surprising truth:

Exact search can be worse than approximate search in high dimensions.

ANN works better because it avoids the entire distance landscape and instead exploits structure:

- graphs

- clusters

- quantization

- routing shortcuts

3.5 ANN Is Not a Shortcut — It’s Survival

ANN indexing exists because:

- brute-force is computationally impossible

- high-dimensional exact search is unstable

- ANN massively shrinks the search space

- ANN enables selective routing (only search relevant shards)

- ANN enables SSD-backed indexes

- ANN allows billion-scale search on normal clusters

Every production vector database relies on:

- HNSW — graph navigation

- IVF — coarse clustering

- PQ / OPQ — compressed, SSD-friendly codes

Flat brute-force is used only for:

- tiny datasets

- evaluation

- debugging ANN recall

Never for real workloads.

Takeaway

Brute-force dense search collapses because of three forces:

1. Compute explosion: 30+ billion FLOPs per query at moderate scale.

2. Memory bandwidth limitations: Hardware can compute fast — it just can’t fetch vectors fast enough.

3. High-dimensional geometry failure: Distances converge → exact search becomes unstable and meaningless.

This is why ANN is not an optimization technique. It is the foundational engine that makes dense search even possible.

4. ANN Indexing: The Real Engine Behind Dense Search

By now it should be clear why brute-force dense search collapses:

- compute explodes

- memory bandwidth becomes the ceiling

- distances converge in high dimensions

This is why every production vector system uses ANN (Approximate Nearest Neighbor) indexing. ANN isn’t an optimization.

ANN is survival. There are three ANN families that matter in modern systems:

- HNSW — graph-based, built for low latency

- IVF — cluster-based, built for scale

- PQ / OPQ — compression-based, built for billion-scale

Let’s walk through them — intuitively and architecturally.

4.1 Flat Search (Baseline Only)

Flat = exact search: compare the query against every vector.

Good for evaluations. Disastrous for production.

- perfect recall

- catastrophic compute cost

- cannot scale

- saturates memory bandwidth

Flat search exists only to measure ANN accuracy. Real systems replace it immediately.

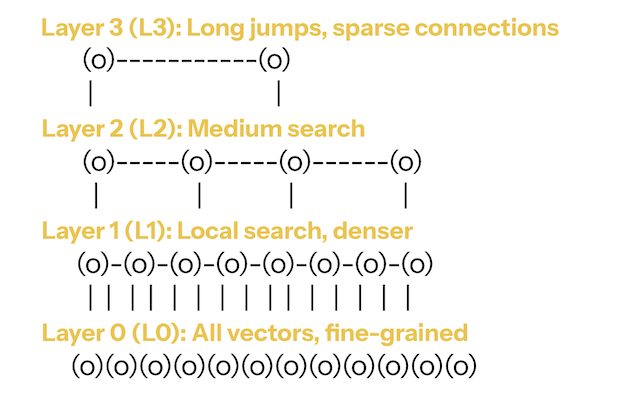

4.2 HNSW — Graph-Based ANN (Fast, RAM-Heavy)

HNSW powers many vector databases (Weaviate, Qdrant, Vespa, FAISS HNSW).

Think of HNSW as a multi-layer graph:

HNSW — Graph-Based ANN (Fast, RAM-Heavy)

HNSW — Graph-Based ANN (Fast, RAM-Heavy)

Top layers = long jumps across the space

Bottom layer = detailed local search

Intuition

- Start high (broad search)

- Move toward better neighbors

- Drop layers

- Resolve locally

Satellite view → street view.

Why it’s fast

- navigates only a tiny fraction of vectors

- top layers prune most of the search space

- excellent cache locality

- latency often < 10ms at moderate scale

Trade-offs

- high RAM usage (vectors + edges)

- insertions mutate graph structure → slow writes

- hard to shard cleanly across machines

- rebuilds are heavy

Use HNSW when: you need single-node, low-latency, read-heavy performance.

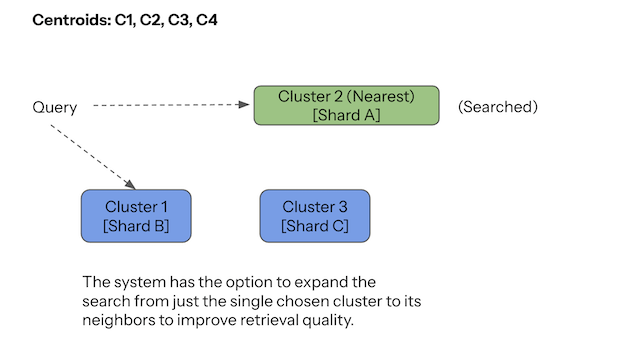

4.3 IVF — Cluster-Based ANN (Scalable, Distributed-Friendly)

IVF (Inverted File Index) is the backbone of distributed vector search — Pinecone, Milvus IVF, FAISS IVF all use it.

IVF turns vector space into clusters:

A vector is stored in the cluster of its nearest centroid.

Query flow

- Compare query to centroids

- Pick closest clusters (e.g., top 1–8)

- Search only inside them

Only small slices of the dataset are touched.

Why it scales

Clusters become natural shards:

Cluster 1 → Node A

Cluster 2 → Node B

Cluster 3 → Node CThis gives:

- predictable routing

- small fan-out

- balanced shards

- controllable recall (via

nprobe) - easy horizontal scaling

Trade-offs

- clustering quality strongly affects recall

- boundary vectors can be tricky

- tuning centroids/clusters is non-trivial

- writes require centroid lookup per insert

Use IVF when: the dataset is large, distributed, and you need controllable latency.

4.4 PQ / OPQ — Compression-Based ANN (Billion-Scale)

PQ compresses vectors the way JPEG compresses images.

Break the vector into blocks → replace each block with its nearest “prototype index.”

Raw subvector: [0.12, -0.02, 0.68, ...]

Nearest prototype: Codebook[180]

Stored as: 180Do this for all blocks → compress 6KB down to ~16–32 bytes.

Why PQ matters

- 600GB raw → ~3GB PQ

- enables SSD-tier search

- makes billion-scale retrieval feasible

Costs

- lower recall (compression error)

- heavier write path (quantization per insert)

- reindexing expensive (codebook rebuild)

OPQ adds a learned rotation step to reduce quantization error.

Use PQ/OPQ when: you need extreme scale, primarily read-heavy workloads, and SSD-backed search.

4.5. The Full Retrieval Stack: ANN + Reranking

The ANN index finds candidates, but it is rarely the final step in a production RAG system. ANN indexes like HNSW and IVF are tuned for high recall and low latency to narrow the search space (e.g., finding the top 100 relevant candidates). These candidates are then often passed to a reranker—a separate, smaller language model (e.g., a cross-encoder)—that performs a final, high-precision ranking. The reranker’s job is to select the best 5-10 final documents for the LLM prompt. This architectural pattern means the true latency of RAG is the cost of ANN traversal + Reranker execution, and both must be engineered for speed.

4.6 Legacy Methods

LSH — hash-based ANN; breaks down in high dimensions.

ANNOY — great for static playlists; weak for dynamic or large datasets.

Included for historical context only.

4.7 Forward-Looking: Where ANN Is Heading (2025+)

HNSW, IVF, and PQ are the backbone today — but indexing isn’t standing still.

As enterprises push toward 100M–1B+ vectors, with filters, multi-tenant setups, and multi-modal data, the indexing layer is evolving in a few predictable directions.

4.7.1. Hybrid vector + structured querying

Real workloads rarely do “pure vector search.” They mix:

- semantic similarity

- metadata and filters (tenant, time, type)

- relational constraints

Index designs are moving from “filter → ANN search” to joint plans where the vector and the filters are handled in a single optimized path. Practically, that means tighter integration with columnar / inverted indexes and smarter planners that understand both sides.

4.7.2. Beyond-RAM indexing (Disk-centric ANN)

RAM-only indexing doesn’t survive at true web scale.

Approaches inspired by DiskANN and SSD-native layouts push more of the index to SSD while still keeping high recall. The emerging pattern:

- RAM holds routing / top-level structures.

- SSD holds bulk vector/posting payloads.

- Queries are tuned to minimize random I/O.

As corpora hit hundreds of millions of vectors, these designs move from “nice-to-have” to mandatory.

4.7.3. Next-gen quantization (PQ → OPQ → adaptive schemes)

Quantization is also evolving:

- better rotations (OPQ-style)

- adaptive or data-aware codebooks

- hybrid schemes that mix compressed and full-precision tiers

The goal is simple: close the quality gap between compressed and uncompressed search so you can keep more data cheap without paying a recall penalty.

4.7.4. GPU-native ANN traversal

As models and retrieval sit closer together, vector databases are increasingly:

- offloading distance computations to GPUs

- exploring GPU-friendly graph/cluster structures

- batching ANN queries tightly for RAG and agents

Expect more architectures where embeddings + ANN + reranking all live on the same GPU pipeline rather than bouncing between CPU and GPU.

4.7.5. Multi-modal index fusion

Retrieval is no longer “just text.”

Indexing layers are being designed to handle and sometimes jointly rank:

- text embeddings

- image embeddings

- audio or video embeddings

- code and other modalities

That doesn’t always mean one giant unified index, but it does mean shared infrastructure that can coordinate multiple embedding spaces in a single retrieval plan.

4.8 Takeaway

ANN indexing is not a single algorithm — it’s a family of architectural choices:

- HNSW for low-latency, RAM-heavy, read-optimized workloads

- IVF for scalable, shardable, predictable distributed systems

- PQ/OPQ for compressed, SSD-backed, billion-scale corpora

And the indexing layer is still evolving toward:

- tighter integration with structured filters

- SSD-native designs for huge corpora

- smarter quantization

- GPU-native pipelines

- multi-modal retrieval

For architects and engineers, the key mental shift is this:

The ANN index is not an implementation detail. It is the vector database’s architecture — and increasingly, a core part of your AI data plane.

5. How Index Choice Shapes System Architecture

Choosing HNSW vs IVF vs PQ isn’t a library-level decision.

It fixes the shape of your system:

- how much RAM you must buy

- how low your latency can realistically go

- how painful writes and reindexing are

- how you shard and route

- how you replicate and fail over

- how you use SSD vs RAM

- how expensive “scale” is over the next 2–3 years

In practice:

Your ANN index is your vector database architecture.

Most teams underestimate this and treat index selection like a tuning knob instead of a structural choice.

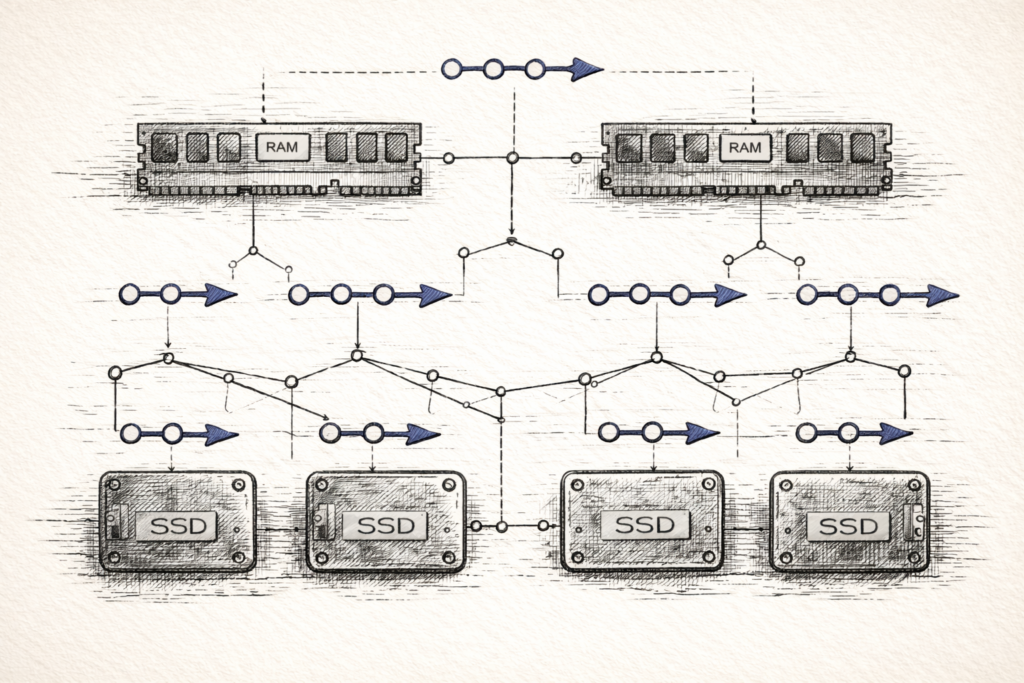

5.1 HNSW Systems — RAM-Heavy, Low Latency, Hard to Scale Horizontally

HNSW architectures are built around one fact:

You get great latency by keeping everything in fast memory and navigating a graph.

That has consequences.

5.1.1 Memory architecture: speed paid in RAM

On an HNSW node, each vector carries:

- the embedding itself (~6 KB at 1536 dims)

- edges across multiple layers

- graph metadata and bookkeeping

By the time you add edges and metadata, you’re at ~6.2–6.4 KB per vector. At 10M vectors:

≈ 62–64 GB RAM (per replica, before caches or overhead)That’s just the index, before:

- replication

- background rebuilds

- other services on the node

This is why HNSW clusters tend to have:

- “hot” nodes where memory pressure spikes

- painful rebuild windows

- crashes when people casually “just add more data”

HNSW is fast because everything is in RAM. That’s the feature and the cost.

5.1.2 Write architecture: read-optimized by design

Inserting into HNSW is graph surgery:

- you traverse the graph to find candidate neighbors

- update edges at multiple layers

- preserve graph invariants and connectivity

- manage concurrency while mutations are happening

That’s slow and noisy compared to just appending to a list.

Operationally, this pushes you toward a pattern:

- ingest into a separate log or staging store

- build or rebuild HNSW indices in batches

- deploy new graph snapshots periodically

The more your workload looks like a stream (logs, events, product changes), the more HNSW fights you.

HNSW systems are read-optimized. Writes are something you manage, not something you do freely.

5.1.3 Sharding architecture: graphs don’t like being cut

HNSW is a single logical graph. Graphs don’t shard cleanly.

To distribute HNSW you end up with compromises:

- replicate the entire graph on multiple nodes (expensive, but simple)

- or maintain multiple partial graphs and rely on a routing layer with heuristics

- plus some form of consistency protocol for writes and rebuilds

Real systems take hybrid approaches (e.g., sharding by collection or tenant, then HNSW per shard), but the theme is consistent:

HNSW is perfect for single-node or small-cluster deployments where you can afford RAM and control ingestion.

Forced horizontal scale and heavy writes get expensive fast.

5.2 IVF Systems — Natural Sharding and Predictable Scale

IVF architectures start with a different premise:

First, partition the space into clusters. Then let clusters define your shards.

That one decision makes distributed design much simpler.

5.2.1 Sharding architecture: clusters → shards

You run k-means (or similar) to get K centroids, then distribute those clusters:

Cluster 1, 2 → Shard A

Cluster 3 → Shard B

Cluster 4, 5 → Shard C

...A query flows like this:

- Compare the query embedding to the centroid set.

- Pick the top-n centroids (

nprobe). - Route the query only to shards that own those clusters.

- Merge the partial results.

This gives you ANN-aware sharding instead of naive “hash-to-node” sharding.

Why this works well in practice:

- shards stay independent and easy to reason about

- routing is deterministic and cheap

- scaling out means “add nodes, move clusters”

- rebalancing means moving whole clusters, not individual vectors

Operationally, IVF systems behave like a normal distributed search engine with a well-defined routing layer.

5.2.2 Memory and storage architecture: predictable footprints

With IVF you can choose where vectors live:

- all in RAM (FAISS-style setups)

- RAM for centroids + metadata, SSD for clusters (Milvus, Pinecone-style)

Because clusters are explicit, you get:

- predictable per-shard memory usage

- relatively stable storage layouts

- simple mental models for “what happens if this cluster grows 5×”

It’s not free, but it’s much easier to budget for than a global graph.

5.2.3 Write architecture: simple, parallel, “always on”

An IVF write is:

- compute embedding

- find nearest centroid

- append to that cluster and update metadata

There’s no global graph mutation, no multi-layer rewiring.

This is why IVF is comfortable for:

- near-real-time ingestion

- continuous updates

- multi-tenant workloads that never “shut down” for rebuilds

It’s still more complex than pure log-structured storage, but much more predictable than HNSW under sustained writes.

5.3 PQ (Product Quantization) Systems — SSD-Backed, Tiered, Designed for Massive Scale

PQ changes the architecture because it changes what you actually store.

Instead of full vectors:

- codebooks live in RAM

- compressed codes live on SSD

- sometimes you keep a small full-precision cache for “hot” items

5.3.1 Memory and storage architecture: RAM for navigation, SSD for bulk

A typical PQ-centric design:

RAM:

- centroids

- codebooks

- routing metadata

SSD:

- compressed codes

- inverted lists / posting lists

Object store:

- cold partitions

- historical indexes

- rebuild artifactsYou navigate in RAM, but pull most payloads from SSD. This lets you:

- keep billions of vectors online

- control RAM strictly

- separate “hot vs cold” data by tier

PQ systems are what you reach for when the dataset size makes RAM-only approaches non-viable.

5.3.2 Write architecture: the heaviest path

A PQ insert does real work:

- embed the document

- split the vector into M sub-vectors

- for each sub-vector, look up the nearest prototype in its codebook

- write the resulting codes to SSD in the right segments

- update the inverted lists / posting structures

If you add OPQ, there’s an extra matrix multiplication step up front.

This is CPU- and IO-heavy, which is why PQ is rarely used for:

- high-rate streaming writes

- constantly shifting domains

It shines when:

- the dataset is very large

- writes are moderate

- reads dominate and memory is the main constraint

5.3.3 Sharding and routing: usually IVF + PQ

In most real systems, PQ doesn’t stand alone — it’s layered under IVF:

- IVF handles clustering and routing to shards.

- PQ compresses vectors within each cluster.

Routing then looks like:

- use IVF to pick clusters / shards

- on each shard, use PQ codes for fast approximate scoring

- optionally rerank a small candidate set using higher-precision vectors

That combination (IVF + PQ) is what enables:

- horizontal scale across nodes

- vertical scale to billions of vectors

- a clean split between RAM (navigation) and SSD (payload)

5.4 Takeaway: Index Choice = System Shape

Summarizing the architectural impact:

-

HNSW →

Low latency, high RAM, slow writes, awkward sharding. Great for small–mid-sized, read-heavy workloads where you control ingestion and want fast agent loops.

-

IVF →

Natural sharding, predictable routing, balanced memory/storage. Ideal for mid–large corpora, multi-tenant systems, and “always-on” enterprise search / RAG.

-

PQ / OPQ →

Compressed, SSD-backed, tiered storage. Designed for billion-scale, cost-sensitive deployments where reads dominate and memory is the main constraint.

Your ANN index choice determines:

- your latency budget

- your RAM and SSD footprint

- your ingestion and reindexing strategy

- your replication and failover patterns

- your operational risk and cost envelope

ANN isn’t an ML detail. It’s an architectural decision that quietly locks in how your entire dense search stack will behave at scale.

Related Posts in This Series

This article is part of a broader series on how vector databases behave in real production systems. You can explore the other posts here:

The Hidden Complexity Behind Scaling Dense Vector Search

Why dense retrieval collapses at scale and what architects must understand about high-dimensional search.

Distributed Vector Search: How Real Vector Databases Scale Beyond One Machine

What changes when ANN search becomes distributed — routing, sharding, replication, and cluster topology.

The Write Path in Vector Databases (It’s a Distributed Systems Problem)

How ingestion, updates, and index rebuilds reshape your system architecture far more than cosine similarity does.

How Vector Databases Fail (And What Architects Must Design For)

A practical breakdown of memory issues, hot shards, tail latency, and why systems fail in the real world.

6. Key Takeaways

Dense vector search looks like an implementation detail — but in modern AI systems, it behaves like a core data-plane dependency with implications across latency, cost, and reliability.

Here are the architectural truths to walk away with:

6.1 Dense Search Determines Whether RAG / Agents Scale

You can improve your prompts or model all day — but if retrieval is slow or inconsistent, the entire system collapses.

Dense search directly drives:

- latency

- stability

- correctness

- agent reliability

Retrieval failure → hallucination.

6.2 ANN Index Choice Is an Architectural Decision

Choosing HNSW vs. IVF vs. PQ dictates:

- how you shard and route queries

- how you replicate

- how you handle writes

- how you reindex

- how you scale across clusters

- how you control costs

The index effectively defines the system’s shape.

6.3 Memory Footprint and Write Path Drive Cost

Most failures are not due to poor recall — but due to:

- memory saturation

- tail-latency spikes

- index rebuild storms

- unbalanced routing

- cluster drift

Dense vector search becomes expensive fast, especially with replicas.

6.4 Reindexing Is a Migration, Not an ML Task

Every embedding upgrade implies:

- re-embedding

- reclustering

- storage rewrites

- routing metadata updates

- dual-write / dual-read windows

This is a distributed database migration, not an ML tweak.

6.5 Scaling Dense Search Is Mostly About Routing

ANN solves local search.

Distributed ANN solves global retrieval.

The index is the first half; the reranking layer is the second. Real-world failures come from:

- hot shards

- poor centroid distribution

- misrouted queries

- drifting clusters

- underprovisioned nodes

Topology matters more than the math.

6.6 Dense Search + Hybrid Retrieval Are Now Infrastructure

This retrieval stack is now as fundamental as:

- the message bus

- the cache

- the index

- the document store

It underpins RAG, copilots, agents, and modern search modernization efforts.

7. References

7.1 Embedding & Semantic Models

Reimers & Gurevych (2019) — Sentence-BERT

https://arxiv.org/abs/1908.10084

Cer et al. (2018) — Universal Sentence Encoder

https://arxiv.org/abs/1803.11175

Devlin et al. (2018) — BERT

https://arxiv.org/abs/1810.04805

OpenAI (2024–2025) — Embeddings API Docs

https://platform.openai.com/docs/guides/embeddings

7.2 ANN Index Foundations

Malkov & Yashunin (2018) — HNSW

https://arxiv.org/abs/1603.09320

Jégou et al. (2011) — Product Quantization

https://lear.inrialpes.fr/pubs/2011/JDS11/jegou_search_pami.pdf

Johnson, Douze, Jégou (2017) — FAISS, Billion-Scale Search

https://arxiv.org/abs/1702.08734

Spotify — ANNOY

https://github.com/spotify/annoy

Indyk & Motwani (1998) — Locality Sensitive Hashing

https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/276698.276876

7.3 Vector Databases & Distributed Search

Pinecone Engineering Blog

https://www.pinecone.io/learn/

Weaviate Engineering Blog

Milvus Docs (LF AI & Data)

Vespa (Yahoo Search)

7.4 Research Surveys (Optional Deep Dives)

Wang et al. (2021) — ANN Survey

https://arxiv.org/abs/1607.00117

Aggarwal et al. (2001) — Distance Concentration

https://www.cs.utexas.edu/~inderjit/public_papers/ann-survey.pdf

Guo et al. (2020) — Dense Vector Search & Index Structures

https://arxiv.org/abs/2005.12877

7.5 Architecture, Scaling & Vector Ops

Meta (FAISS)

https://github.com/facebookresearch/faiss

AWS OpenSearch KNN Plugin

https://opensearch.org/docs/latest/search-plugins/knn/

Google ScaNN (2020)