A systems-level explanation for engineers, architects, and anyone building RAG, search, or agent infrastructure.

Dense retrieval looks clean on paper.

You take an embedding model, generate vectors, drop them into a vector database, and let an ANN index handle the rest.

But once you go beyond a single machine, dense search becomes something very different: a collision point between geometry, distributed systems, memory constraints, indexing, and operational engineering.

Traditional search engines deal with two or three of those.

Vector search touches all of them at once.

This is why scaling dense retrieval is not simply “make the index bigger” or “add more nodes.” It is a multi-layer architectural challenge.

Below is the deeper breakdown of why dense search resists simple scaling — and what makes real-world systems behave the way they do.

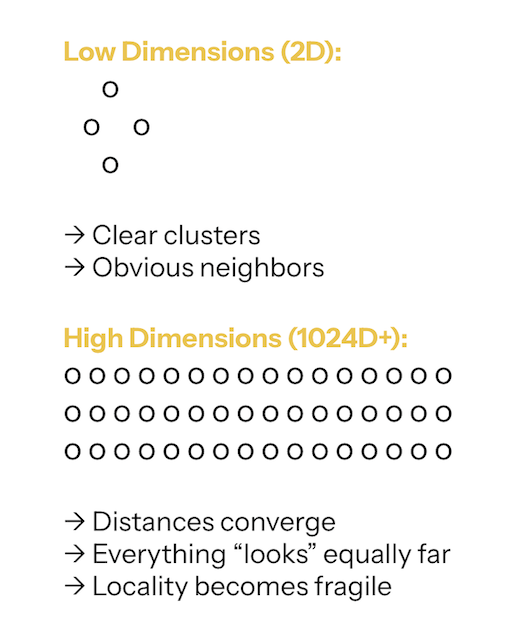

1. High-Dimensional Geometry Is Inherently Hostile

Dense vector search lives in high-dimensional space — often 768D, 1024D, or 1536D.

In these spaces: Distances compress, Nearest neighbors are barely closer than unrelated points, Clustering becomes unstable, Locality becomes fragile.

There is no “obvious” neighborhood structure to lean on.

Everything is probabilistic. This is often exacerbated by the initial choice of distance metric (e.g., Cosine Similarity vs. L2 distance), a decision that must align with both the embedding model and the underlying hardware's optimization capabilities.

This has real consequences:

- Exact search becomes meaningless outside tiny datasets.

- Brute-force search, while conceptually simple, becomes explosively expensive.

- All practical systems must rely on approximate indexing.

- Routing decisions (“which shards should I query?”) are based on probabilities, not guarantees.

The geometry itself creates the instability that the rest of the system must counteract.

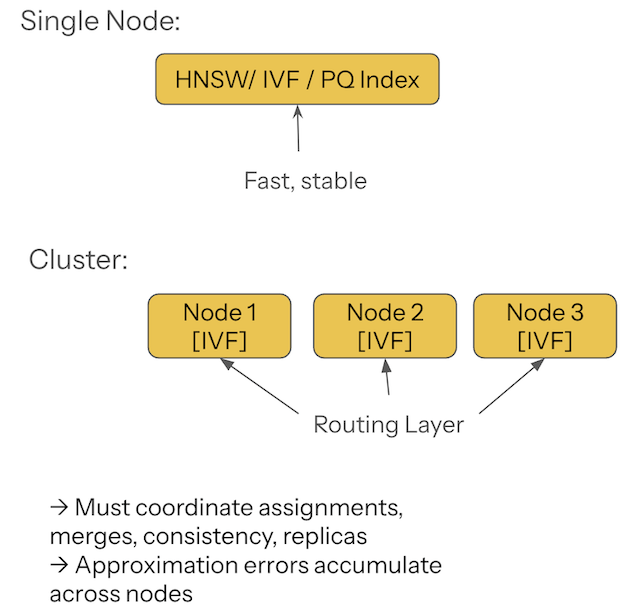

2. ANN Indexes Solve Local Search, Not Global Search

HNSW, IVF, PQ, and OPQ are brilliant inventions — but designed for single-node environments. On one machine, they behave beautifully. Across a cluster, they introduce a second set of problems:

- Nodes must agree on cluster assignments.

- Routing metadata must remain consistent.

- Partial results must be merged without compounding approximation errors.

- Replicas must converge despite write operations.

- Reindexing must remain coordinated across the entire fleet.

In other words:

ANN indexes accelerate search locally.

Distributed vector databases must fix everything else globally.

This separation of concerns is what makes scaling so tricky.

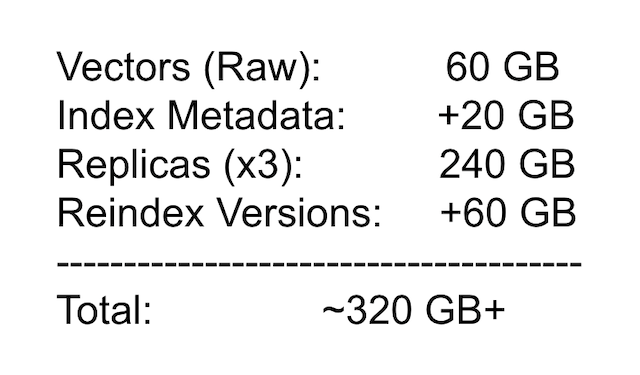

3. Memory Footprint Becomes the Architectural Lodestar

Memory is the real constraint, not compute.

A 1536-dimension float vector is roughly 6 KB uncompressed.

Ten million vectors already push ~60 GB raw — before index overhead, replicas, or historical versions.

Factor in:

- graph layers (HNSW)

- IVF partition metadata

- PQ codebooks

- multiple versions during reindex

- replication per shard

…and your memory footprint quickly spirals past 100–300 GB.

Note that the indexing algorithms themselves are often designed to mitigate these memory constraints. For instance, Product Quantization (PQ) is primarily a lossy compression technique used to shrink vectors down (e.g., from 6KB to 1KB) by trading off search precision for massive memory savings. Similarly, IVF (Inverted File Index) works by reducing the search scope, effectively reducing the necessary hot data in RAM. The memory constraints are so severe that the algorithms must also double as compression and routing tools.

The system stops being governed by algorithms and starts being governed by RAM economics:

Where do we put the vectors?

Where do we put the centroids?

How many replicas can we afford?

Which parts can live on SSD without affecting latency?

What must remain hot in RAM?

Systems don’t degrade gracefully when memory runs tight.

They collapse.

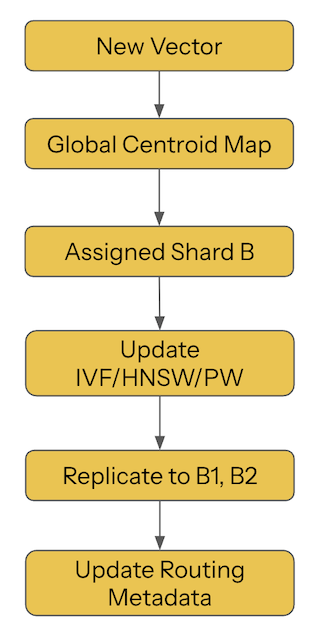

4. The Write Path Complicates Everything

Vector search isn’t static. Documents arrive, expire, drift, and get re-embedded as models evolve.

Embeddings shift. Codebooks must stay consistent. Graph edges must maintain navigability. Shard placement must adapt as distributions change.

Writes touch nearly every structure:

- cluster assignments in IVF

- graph connectivity in HNSW

- compressed blocks in PQ

- routing tables

- replica buffers

- SSD layouts

- background compaction jobs

Because embeddings depend on relative geometry, not absolute identifiers, even a small shift in the vector space forces recalculation of many structural relationships.

Every write is a small, distributed geometric event.

5. Reindexing Is a Cluster Migration, Not an ML Job

At some point, your embedding model improves — and you need to reindex everything.

This is not an optional “nice to have.” It is an unavoidable part of maintaining relevance and semantic accuracy.

Reindexing means:

- re-embedding millions or billions of documents

- reclustering IVF layouts

- regenerating PQ codes

- rebuilding HNSW layers

- rewriting shards

- draining and refilling partitions

- running dual-read / dual-write transitions

- coordinating replicas

- recalibrating routing metadata

Few engineers realize this when they first start using vector DBs: Reindexing is not ML work. It is distributed system migration work.

It resembles elasticsearch rebalances, sharded DB schema upgrades, and multi-region failovers far more than it resembles “run inference again.”

6. Dense Search Lives Inside a Strict Latency Budget

RAG systems, chatbots, and agents all have hard latency caps.

You typically have 100–150 ms end-to-end:

- 10–50 ms for embeddings

- 5–30 ms for vector search

- 5–15 ms for reranking

- 30–80 ms for LLM reasoning

There is no room for sloppy fan-out patterns, random broadcasts, or unstable tail latencies.

Search must:

- hit the right shards

- efficiently execute a scatter-gather fan-out pattern

- perform a fast K-way merge of partial results efficiently

- avoid node hopping and unstable tail latencies

- maintain recall under low latency

- deliver predictable behavior every single time

Dense search isn’t just an algorithm — it’s a critical path stage.

If it stutters, the entire pipeline misses the SLA.

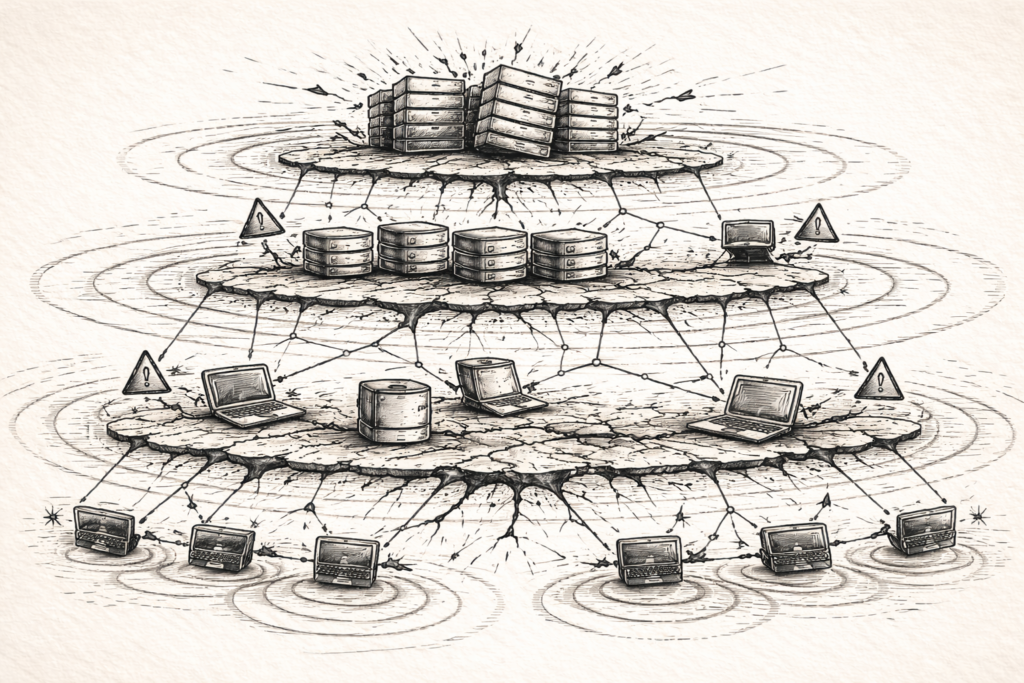

7. Distributed Systems Introduce Non-Local Failures

Once dense search spans a cluster, failures stop being local.

A hot shard increases latency for unrelated queries.

A stale routing map misroutes entire workloads.

An overloaded PQ node spikes tail latency globally.

Imbalanced clusters degrade recall across domains.

SSD wear levels introduce unpredictable slowdowns.

Replica inconsistency creates nondeterministic results.

One shard drifting leads to an entire fleet rebuild.

Dense search doesn’t fail like a simple service. It fails topologically, in ways that ripple through the system.

This is why vector DB reliability engineering feels closer to:

- distributed caching

- multi-shard OLAP engines

- search engine relevance tuning

- cluster-wide failover management

than to “just a database.”

Final Takeaway

Dense vector search is hard to scale not because embeddings are complicated, but because the system is a single, intertwined entity with five layers:

- A Geometric Space: Inherently unstable and hostile.

- An Approximate Index: Brittle and memory-hungry.

- A Memory Subsystem: The expensive architectural bottleneck.

- A Distributed Routing/Sharding Architecture: Volatile and prone to cascading failures.

- An Operational Pipeline: Non-trivial SRE work required for writes, rebuilds, and drift management.

Traditional databases isolate these concerns. Vector systems bind them together. Every decision—from sharding to indexing—simultaneously affects all five layers. The architectural cost of dense retrieval is not in the algorithm; it is in the operational discipline required to keep a complex, geometry-bound, distributed system running at low latency.